University Campus Map

Interactive Wayfinding Application

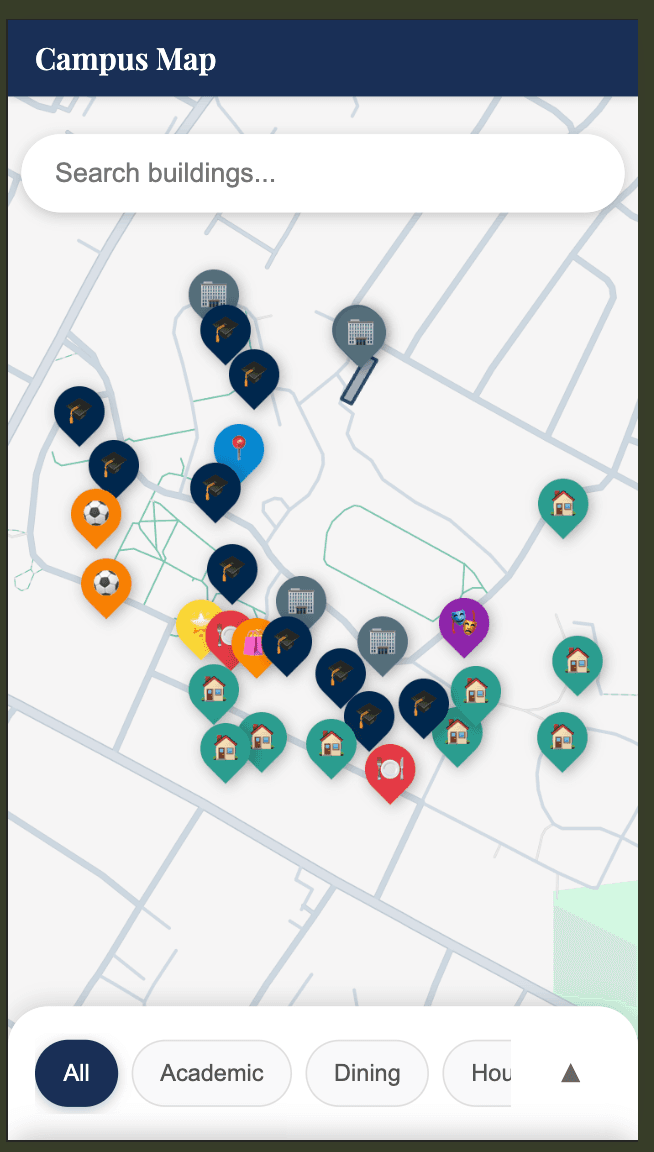

I founded and led the development of a new interactive campus map for St. Edward's University after identifying a core navigational need. I owned the end-to-end UX/UI design, directed a team of student assistants, and used Lean UX to iterate fast with continuous feedback from university departments.

Key Results

The Problem

During my first week at St. Edward's, I watched a parent and prospective student wander the quad for nearly 10 minutes looking for the admissions building—while holding a paper campus map. That moment made the problem obvious.

The existing campus map was a static PDF image. No search. No filtering. No way to know if a building had an accessible entrance until you got there.

From my interviews with students and stakeholders, the pain was clear:

"I just follow whoever looks like they know where they're going." — Freshman

"I called ahead to ask about wheelchair access. They didn't know." — Student with mobility needs

"I've worked here 3 years and still can't find HR." — Staff member

People were spending minutes fighting with a static image just to find a building. Most gave up and asked someone instead.

The Solution

I designed an interactive campus map guided by three core principles:

1. Information When You Need It

Show details on demand, not all at once. A map cluttered with 200 markers is as useless as no map at all.

2. Never Lose Context

Users should always know where they are relative to their destination. Details should augment the map, not replace it.

3. Accessibility is Visible

Accessibility information shouldn't be buried 3 clicks deep. It should be as prominent as hours and phone numbers.

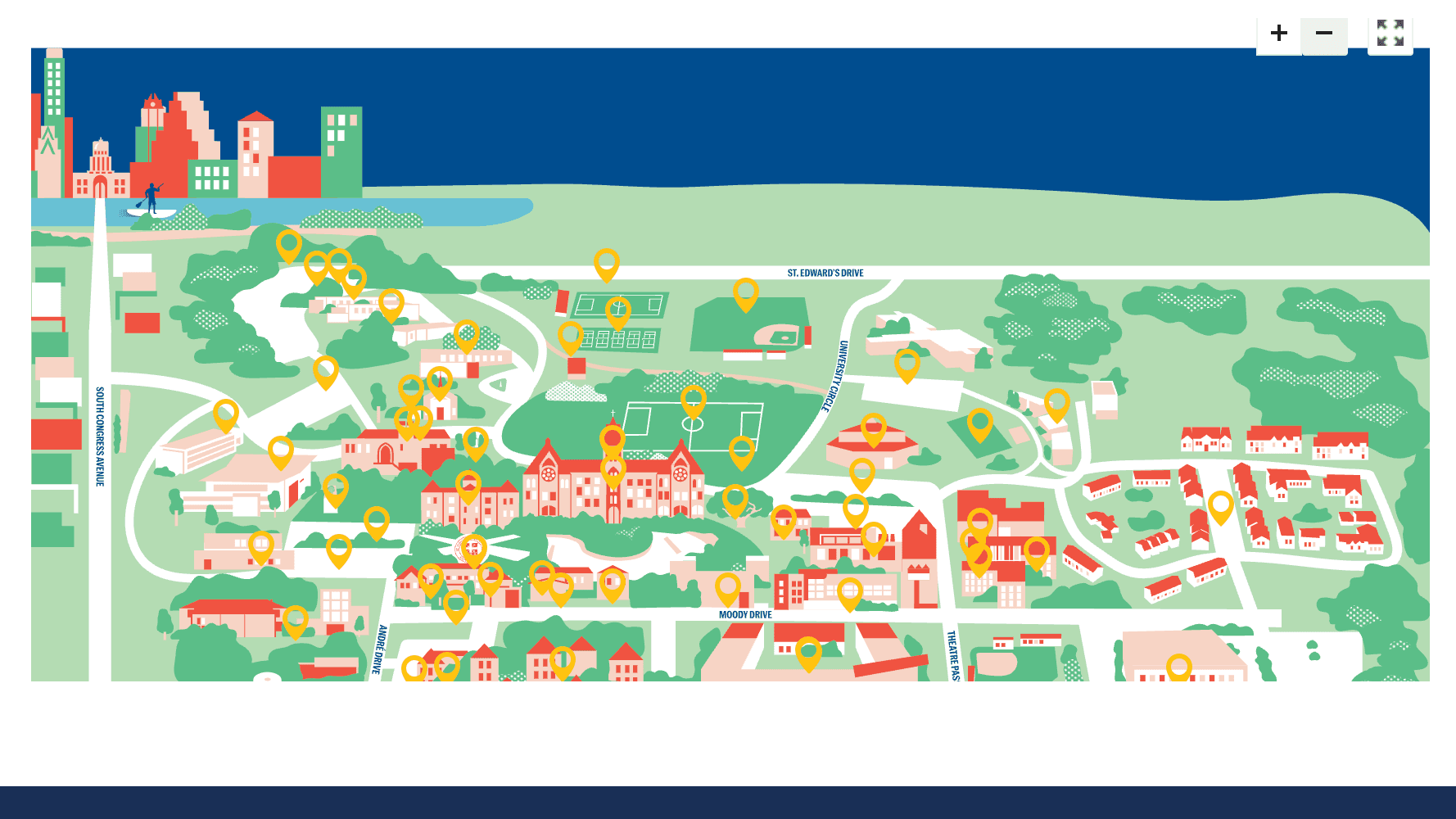

The result: a mobile-first wayfinding app with search, filtering, and detailed location sheets—built on Google Maps but designed specifically for campus navigation.

The Process

User Research

User Research

I started by understanding who uses campus maps and why—which turned out to be more complex than I expected.

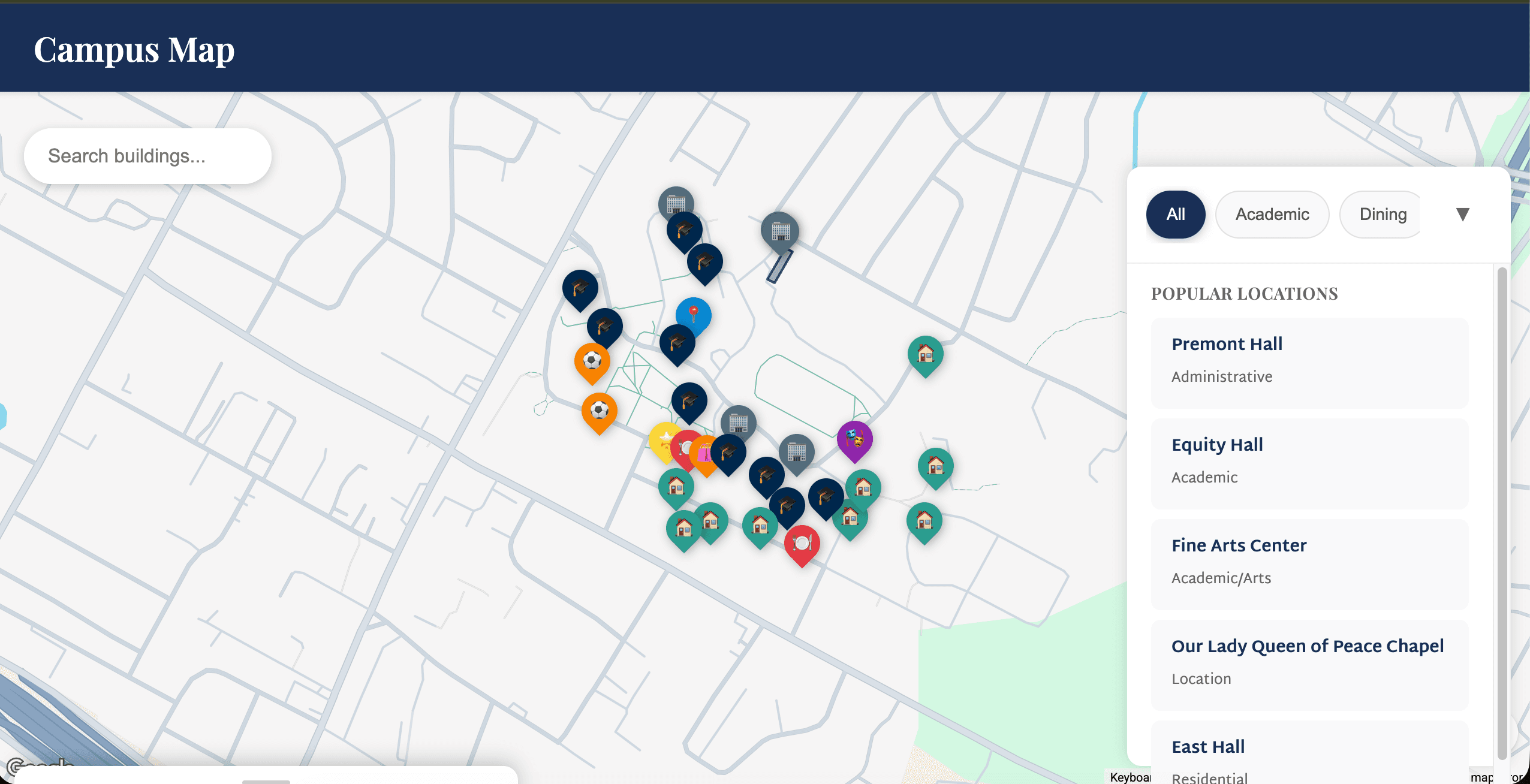

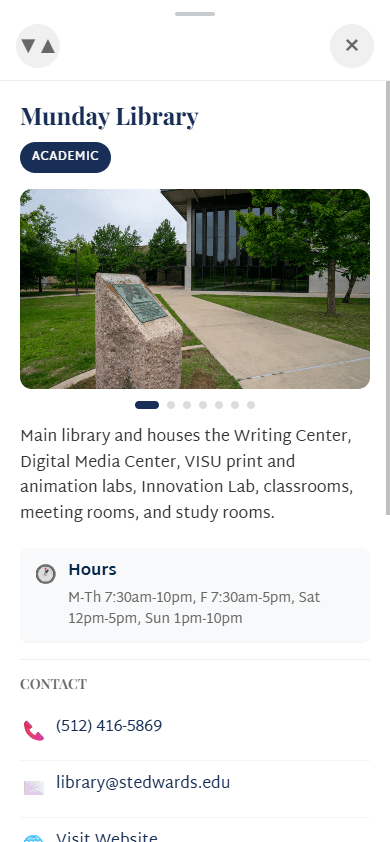

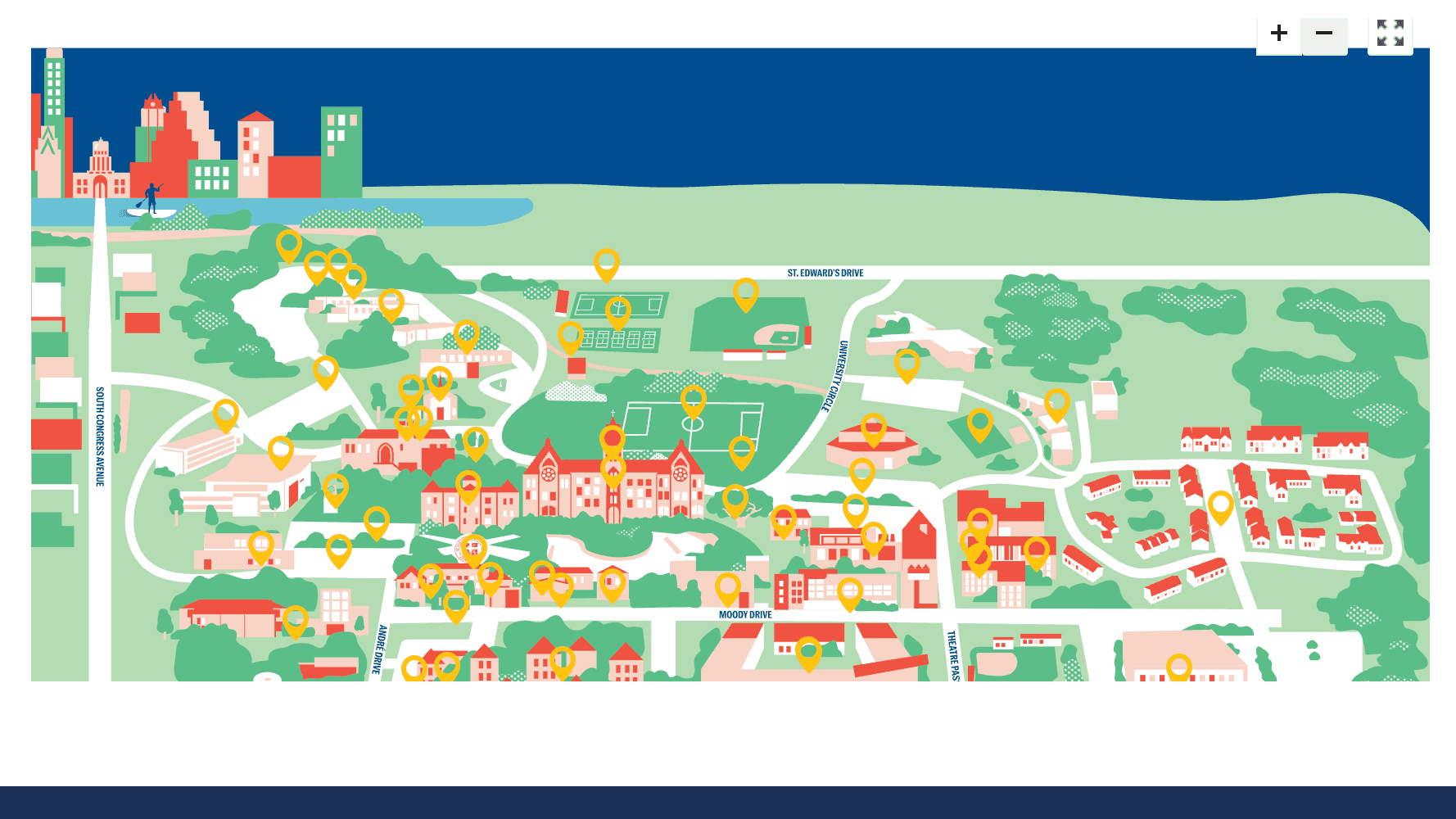

First, I evaluated the existing campus map (shown below). It was a static illustrated image: no search, no filtering, no accessibility info, and it loaded as a 4MB file that took 8+ seconds on mobile. Users had to visually scan the entire image to find anything.

Research Conducted:

Surprising Insight:

I assumed new students would be the primary users. But staff kept coming up in conversations too—they knew their own building but struggled to find offices in other buildings.

"I've been here three years. I still don't know where half the buildings are." — Sarah, Administrative Coordinator

Another surprise: The #1 request wasn't "better design." It was "tell me if there's an elevator before I walk across campus in July heat." Accessibility information was a critical unmet need.

User Personas

User Personas

From my interviews, four distinct patterns emerged. These aren't invented personas—they're composites of real people I spoke with, using their actual quotes and behaviors.

Maria

Freshman · Biology Major · Age 18

"I have 10 minutes between classes and I'm already lost."

🎯 Goals

- •Find classroom buildings quickly between classes

- •Discover dining options and study spaces

- •Learn campus layout before first week

😤 Frustrations

- •Static maps don't show where I am

- •Can't search for buildings by name

- •Asking for directions feels embarrassing

David

Parent · Campus Visitor · Age 45

"I want to explore campus with my daughter without getting lost."

🎯 Goals

- •Navigate to admissions office

- •Find parking and dining options

- •Get a sense of campus amenities

😤 Frustrations

- •Unfamiliar with campus layout

- •Paper maps are hard to read

- •Limited time for the visit

Sarah

Administrative Coordinator · 3 years on campus · Age 34

"I know my building, but I need to find HR in a building I've never been to."

🎯 Goals

- •Locate specific offices and services

- •Find meeting rooms in unfamiliar buildings

- •Direct visitors to correct locations

😤 Frustrations

- •Knows general layout but not every building

- •No way to see what services are where

- •Building names vs. common names confuse visitors

Alex

Junior · Uses wheelchair · Age 22

"I need to know if there's an accessible entrance BEFORE I get there."

🎯 Goals

- •Find accessible entrances and elevators

- •Plan routes that avoid stairs

- •Locate gender-neutral bathrooms

😤 Frustrations

- •Accessibility info is never on maps

- •Has to call ahead to ask about entrances

- •Gets stuck at buildings with only stairs

Research Synthesis: Key User Needs

Research Synthesis: Key User Needs

Synthesizing research across all personas, I identified six core needs that would drive design decisions:

🔍Quick Search

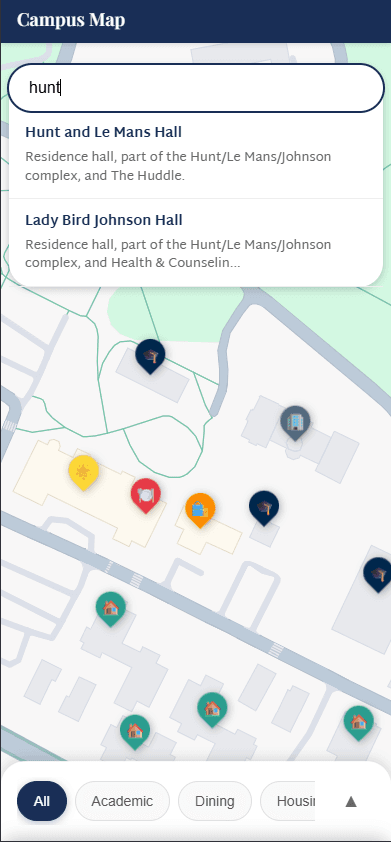

Maria needs to find a building in seconds, not minutes. Search must be fast and forgiving of typos.

🗺️ Visual Context

David needs spatial understanding. An interactive map provides orientation that text directions cannot.

📋Detailed Information

Sarah needs to know what services are in each building, not just where it is.

♿Accessibility Information

Alex needs to know about accessible entrances and elevators BEFORE arriving—not after getting stuck.

🧭Browsing & Discovery

New students benefit from exploring campus virtually to build mental maps before orientation.

📱Mobile-First Design

Most people access campus maps while walking. The interface has to work one-handed on a phone.

These needs informed a design strategy built around progressive disclosure and mobile-first interaction patterns.

Wireframing & Interaction Design

Wireframing & Interaction Design

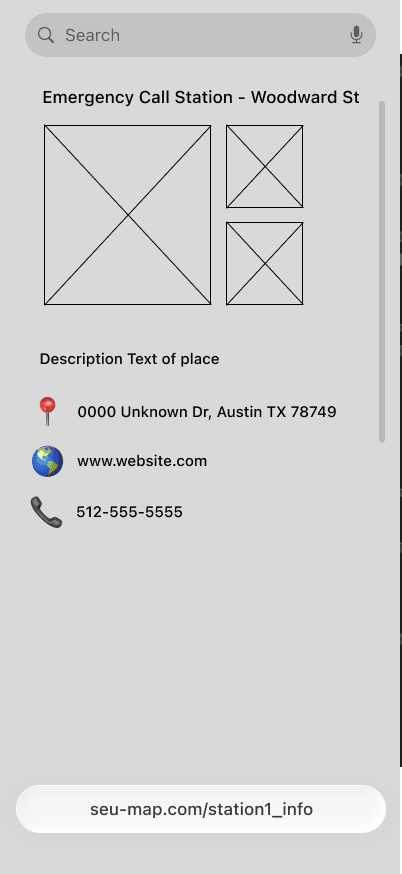

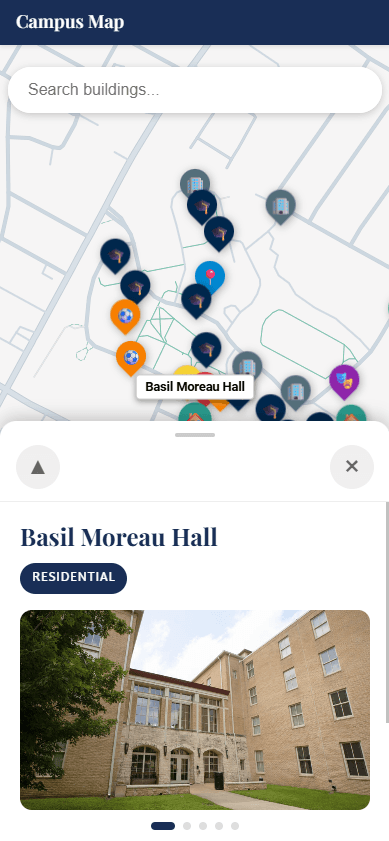

I explored multiple interaction patterns through mid-fidelity wireframes, testing each with the persona needs in mind. The key challenge: how do you show detailed building information without losing map context?

I iterated through five different patterns (shown below). Each iteration taught me something new about what users needed:

Iteration 1

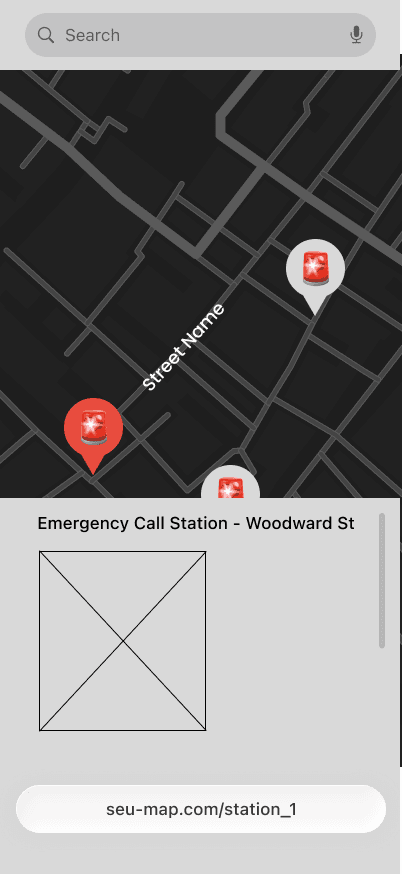

Detail View Exploration: Full-screen location card showing all information (photo gallery, description, address, contact). Problem: Users lose map context entirely—bad for wayfinding.

Iteration 2

Bottom Sheet Pattern: Location details slide up from bottom while map stays visible. Winner: Users can see where they are while reading building info. Familiar pattern from Apple/Google Maps.

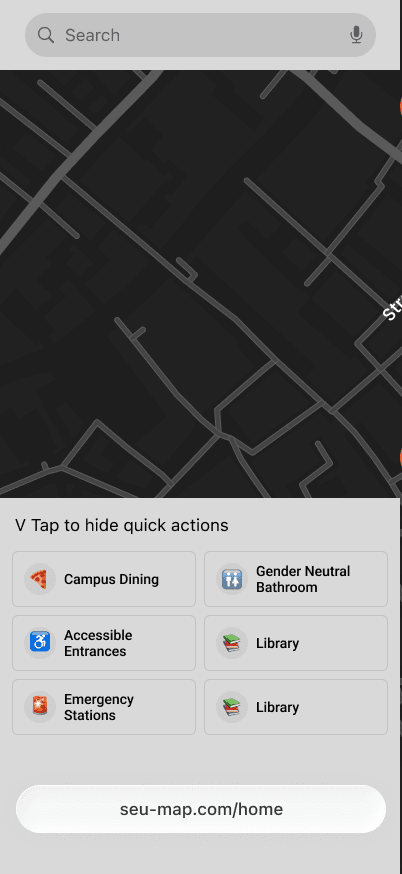

Iteration 3

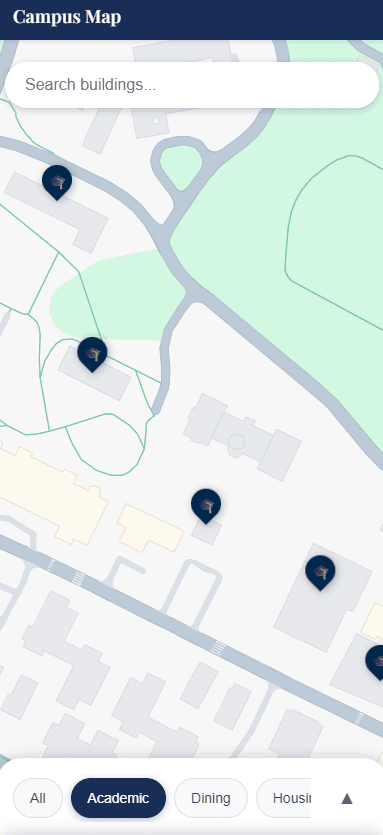

Quick Actions Menu: Expandable panel with category shortcuts (Dining, Accessible Entrances, Library). Addresses Maria's need to find places fast without browsing the full map.

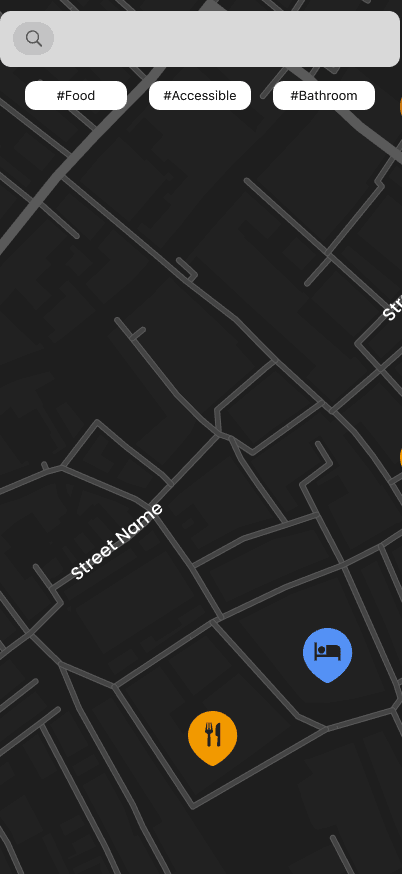

Iteration 4

Tag-Based Filtering: Filter chips (#Food, #Accessible, #Bathroom) let users combine filters. Critical for Alex who needs to find accessible AND dining options together.

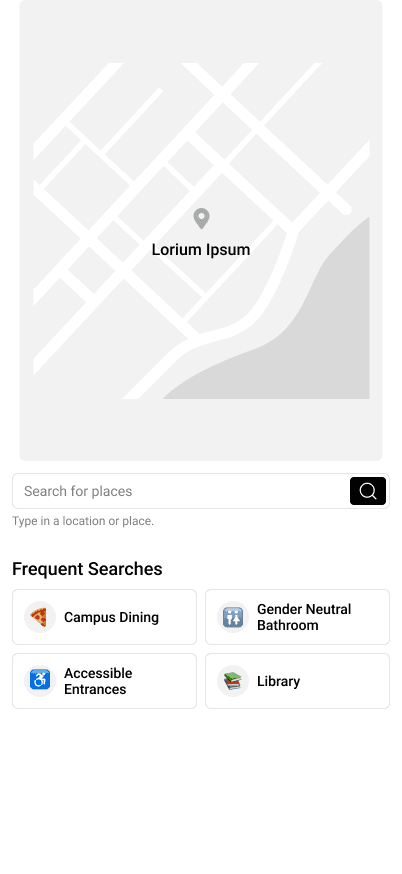

Iteration 5

Final Search Pattern: Search bar with "Frequent Searches" shortcuts below. Testing showed users expected search at top, quick actions at bottom—following mobile conventions.

Key Design Decisions

Key Design Decisions

Not every idea worked. Here are the decisions I made—and the ones I had to kill.

✗ KILLED: Full-Screen Location Cards

My first instinct was to show all building info in a full-screen modal (Iteration 1 above). When I tested it, users immediately tried to get back to the map. They needed to see WHERE they were going, not just read ABOUT it. I switched to a half-height bottom sheet that keeps the map visible (Iteration 2).

✗ KILLED: Category Tabs at Top

I initially placed category filters (Academic, Dining, Housing) as tabs at the top. On mobile, they were hard to reach one-handed. Moving filters to a bottom quick-actions menu (Iteration 3) made a noticeable difference in how often people used them.

✓ KEPT: Minimal Google Maps UI

I disabled Google Maps' default controls (zoom buttons, street view, map type). Stakeholders pushed back—"users expect those controls." But in testing, nobody tried to use them. They cluttered the interface without adding value.

✓ KEPT: Required Accessibility Info

I made accessibility information mandatory for every location in the database—even if the answer was "no accessible entrance." This was controversial with the content team, but it meant users with disabilities could trust the information was complete.

Accessibility: A First-Class Feature

Accessibility: A First-Class Feature

During research, I interviewed a student who uses a wheelchair. She told me: "I've missed classes because I got to a building and there was no ramp. Now I just leave 20 minutes early for everything."

That conversation changed my entire approach.

The Problem:

Most campus maps treat accessibility as an afterthought—a small icon buried in a details page, if it exists at all. Users with disabilities have to call ahead or show up and hope.

My Approach:

Accessibility features are displayed at the SAME visual level as hours and contact info (see the mobile interface below). If a building has no accessible entrance, we say so explicitly. No hunting required.

Validation:

I tested with 2 users who have disabilities—one wheelchair user and one user with low vision who uses VoiceOver. The wheelchair user said: "This is the first campus map I could actually use independently."

Technical Accessibility:

Accessibility isn't a feature I tacked on at the end—it shaped the design from the start.

Usability Testing & Iteration

Usability Testing & Iteration

I ran informal usability tests with students and staff to see where the design broke—and how to fix it.

Task 1: "Find the library"

✗ Problem: Users typed "Munday" (the common name) but got no results. The database only had "Munday Library."

→ Fix: Added nickname matching. "Munday," "Munday Library," and "Library" all work now.

Task 2: "Find an accessible entrance to the dining hall"

✓ Success: Users completed this quickly. Prominent accessibility info worked as intended.

Task 3: "Find where to get your student ID"

✗ Problem: Some users missed the filter buttons entirely. The gray-on-gray contrast was too subtle.

→ Fix: Increased button contrast and added a subtle border.

Unexpected Finding:

Users tried to tap the collapsed bottom sheet to expand it, but it required a swipe. I added a "tap to expand" affordance.

This is still an ongoing process—I'm continuing to test and iterate as the MVP evolves.

Final Design

Final Design

The final design addresses each persona's core needs:

👩🎓 Maria → Instant search finds buildings in seconds, mobile-optimized for walking

👨👩👧 David → Category filters and building photos help visitors discover campus

👩💼 Sarah → Detailed info shows services, offices, and both official/common names

♿Alex → Accessibility features displayed prominently, not buried in menus

The screens below show the complete user journey: Search → Filter → Select → View Details.

Before & After

Before & After

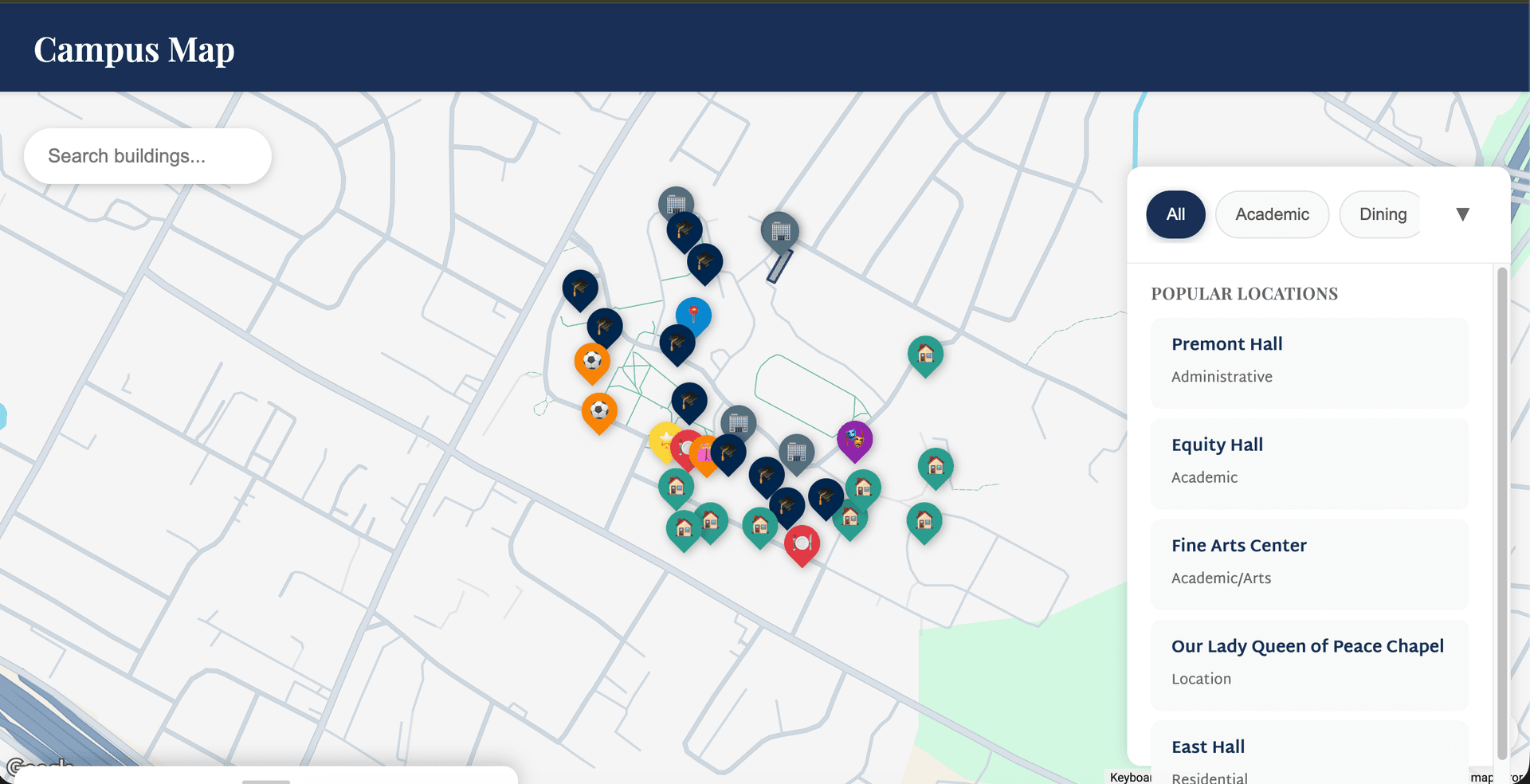

Comparing the old static map with the new interactive wayfinding system shows the full scope of the transformation:

Iteration 1

BEFORE: Static illustrated image—no search, no filtering, no accessibility information, and no mobile optimization.

Iteration 2

AFTER: Interactive Google Maps integration with instant search, category filtering, prominent accessibility features, and mobile-first design. Built with Lean UX methodology and still being iterated on.

Outcomes & Impact

The MVP launched in Fall 2025 and is live on campus. The project is ongoing—I'm still iterating based on feedback and testing.

📡Where It Stands Now:

🔧What I'm Still Working On:

🎯What This Project Taught Me:

I identified the need for this project myself and built it from nothing. I pitched the idea, led a team of student assistants, coordinated with faculty stakeholders, and owned every design decision. Going from "this should exist" to a live product people actually use was the most valuable experience of my degree.

Retrospective

How I Work:

I applied Lean UX throughout this project—short cycles, continuous feedback, and getting a working product in front of people as fast as possible instead of designing in isolation. I also leveraged AI tools to accelerate the MVP build, which let me move faster on the engineering side and stay focused on design decisions.

My Team:

I directed a team of UX students from my professor's topics class. I assigned them to verify building data, photograph campus locations, audit accessibility features, and design icons and logos. I coordinated with faculty stakeholders across IT, Facilities, and Student Services to make sure the map actually served the university's needs.

The Hardest Conversation:

Convincing the content team to require accessibility information for EVERY building—even if it meant more data entry. I showed them the interview quotes about students with disabilities not knowing if buildings had ramps. They agreed.

What I Learned:

1. Stakeholder Pushback is Data

When people resist a feature, it usually means I haven't communicated the research well enough. Once I shared the user quotes, the content team became advocates for mandatory accessibility fields.

2. Constraints Breed Creativity

No budget meant I couldn't use fancy prototyping tools. I tested with paper prototypes first, which actually led to faster iteration.

3. Leading a Team is a Design Skill

Directing student assistants taught me that clear communication and good delegation are just as important as wireframes. If someone doesn't understand WHY they're doing data entry, the data quality suffers.

What I'd Do Differently:

Spicy Boys Food Truck

Self-Service POS System (UX Case Study)